The History of the Piriaka Power Station:

A Legacy of Hydropower

Piriaka was once expected to be a major township, chosen by the government for its Crown land status. However, Taumarunui grew instead, fueled by railway construction and riverboats. It became a borough in 1910 but didn’t have electricity until 1924, thanks to the Piriaka Hydro-Electric Power Station.

Building the station wasn’t easy—early funding proposals were rejected, and financial setbacks delayed progress. However, in 1921, a loan was approved, and construction began. The station officially opened in 1924, delivering hydro power to Taumarunui.

Over the years, Piriaka has expanded and adapted, including a second powerhouse in 1971 that doubled output. Today, the station remains a testament to vision, perseverance, and innovation in New Zealand’s energy history.

1. Taumarunui’s Early Business Hub

In 1901, Taumarunui’s business district was emerging alongside the railway's progress. This view shows temporary shelters alongside the first traders’ larger buildings serving construction workers. On the far right, George Steadman’s bakery sits sideways, while the black building is A.J. Langmuir’s first general store, later known as Fanthorpe’s Corner. His store stands at the intersection of Hakiaha and Manuate Streets, near Hakiaha’s Hall (later Kings Picture Theatre). A well-worn track leads to the Native Village, with the Whanganui and Ongarue Rivers meeting at Cherry Grove/Ngahuinga in the background.

2. Prime Minister Massey Opens Piriaka Hydro-Electric Scheme

On 21 March 1924, at 3:00 pm, Prime Minister Rt Hon W.F. Massey addressed the crowd at the official opening of the new hydro-electric scheme in Piriaka. The New Zealand Herald called it “a red-letter day” for Taumarunui, marking a major step forward in the district’s rapid progress. However, convincing ratepayers that electricity was the future—and affordable—had been a challenge.

3. The Struggle to Establish a Hydro-Electric Scheme

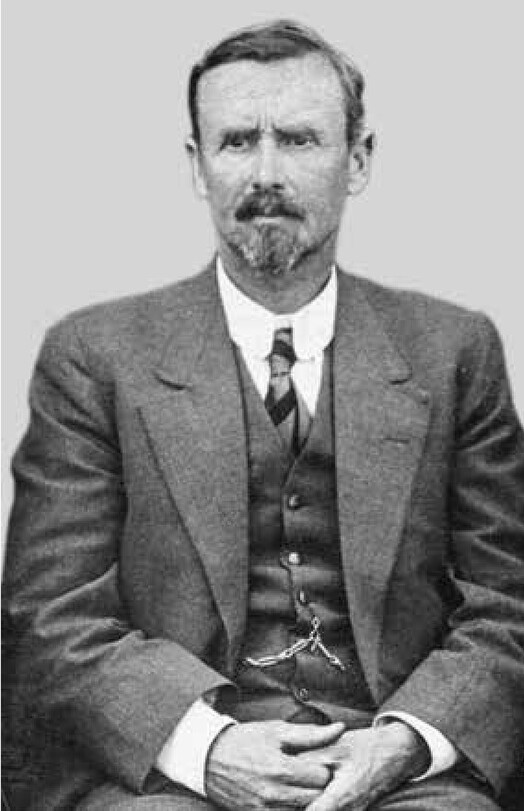

Launching a hydro-electric scheme was no easy task. Although local discussions had shifted toward hydro power by the late 1910s, early attempts faced resistance. During his 1917–1919 mayoral term, Alexander Laird championed the idea and identified Piriaka as an ideal site. However, in 1919, ratepayers rejected the initial loan proposal.

A breakthrough came in 1921 when a licence was granted to use the Whanganui River for electricity generation. A second loan proposal passed overwhelmingly, securing support for the project. But financial turmoil soon followed, as economic downturns dried up funding sources. The council struggled to secure a loan but eventually gained priority over other borrowers in August 1921, keeping the project alive.

Alexander Smith Laird, Taumarunui’s mayor from 1917 to 1919, had set the ball rolling.

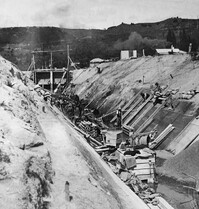

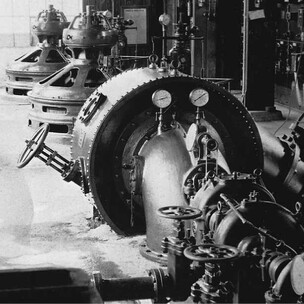

4. Surge Chamber and Penstock Construction

After horse-drawn teams excavated the intake canals, water was directed to the control gates before flowing through a 750-foot-long open canal into a screen chamber. From there, it entered a 9-foot-diameter, 800-foot-long reinforced concrete pipeline leading to the surge chamber.

The surge chamber stood 42 feet above the normal tailrace level with an operating head of 25 feet. Water then passed through the turbine system, where scroll cases and wicket gates regulated flow before it exited into the tailrace.

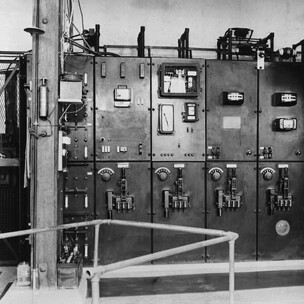

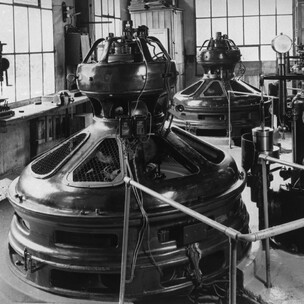

5. Inside the Machine Hall

Each turbine powered a 250 kW alternator, with electricity stepped up for transmission. The machine hall housed two vertical Francis turbine-driven alternators with oil-pressure speed governors. The main switchboard included a synchronization section.

A 35 hp horizontal Francis turbine powered the municipal water supply pump, supplying Manunui and Taumarunui. Added in 1934, it remained in use until a new borough intake from the Whanganui River at Matapuna was commissioned in 1958.

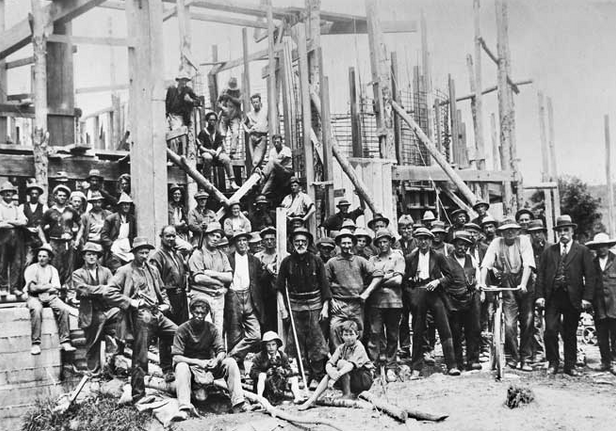

6. Every Man and His Dog Made the News

A group of 53 unidentified workmen—along with two young lads and their dog—was captured on film by Kakahi photographer J.W. Plotnicki during the surge chamber’s construction. Work began around August 1922, with Hay & Vickerman appointed as construction engineers and H. Langdon as the resident construction engineer.

The project, including the headworks, canal, pipeline, powerhouse, and reticulation, was completed through day labor and small contracts.

7. Henry McLeod’s Legacy

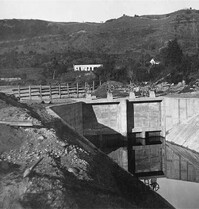

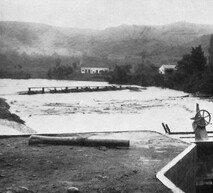

8. Flood of 1924 Tests the New Power Plant

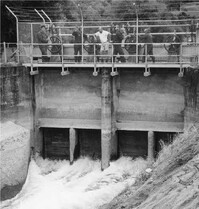

Just 16 days after Taumarunui’s new hydro-electric plant opened, an exceptionally heavy flood hit on 5 April 1924. Water rose within two feet of the powerhouse floor but caused no damage.

The “log stop” (pictured) was a remarkable sight, with logs stacked high under immense pressure. It withstood the flood’s force exceptionally well, sustaining minimal damage.

9. Expanding Taumarunui’s Power Generation (1968–1971)

In 1968, plans were made to expand the powerhouse by adding a new station to the original penstock. A bifurcation in the penstock directed water to a newly installed low-head turbine.

The new horizontal Kaplan turbine, rated at 1.2 MW, more than doubled the station’s output by using additional water when available. Commissioned in January 1971, the plant initially supplied 40% of the district’s electricity demand, despite minor initial issues.

The 2024 view shows the old and new powerhouses alongside their respective surge chambers—the original are images 1 & 2, the newer powerhouse is image 3.

10. Piriaka’s Weirs: Managing Water Flow

Piriaka has three weirs that divert water toward the headworks and intake screens. These low dams are designed to withstand floods while directing water into the intake, where floating booms and mechanical screens remove debris. Unused water flows down the original riverbed.

Over the years, the weirs have required little maintenance—a testament to their robust design and construction.

11. Upgrading the Intake Structure

The intake structure at the canal’s start has undergone many improvements over the years. Originally, operators used long steel rakes to clear debris from the screens. Later, mechanical screen cleaners were installed to lift heavy logs.

A major improvement was shutting down the station when debris levels rose, allowing it to be diverted over the weirs instead of clogging the intake screens. Once river levels dropped and water cleared, the station was restarted after refilling the canal.

Get to know us

Find out how we provide value to our local community